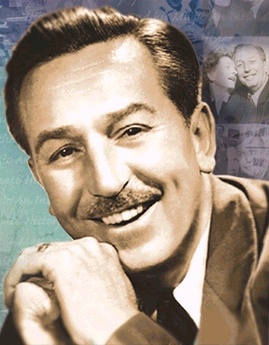

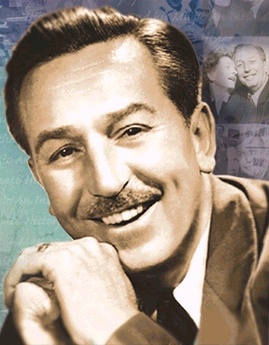

Faith in Disney

Click on the image for an excellent resource regarding Walt Disney's beliefs.

Image courtesy of JustDisney.com.

Faith I have, in myself, in humanity, in the worthwhileness of the pursuits in entertainment for the masses. But wide awake, not blind faith, moves me. My operations are based on experience, thoughtful observation and warm fellowship with my neighbors at home and around the world.

-- Walt Disney

This is the term paper I wrote for my History of Animation class, Winter 2003. Your feedback is welcome, although, as the class is long since over, it might not do too much good! :) It's a sort of long paper, but it's nice. I hope you like it!

Walt Disney Feature Animation has produced several stellar pieces of work. From Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to Treasure Planet, Disney's films have stretched the boundaries of just how far animation can go. Disney has become a household name, a symbol of quality family entertainment. On family entertainment, Disney even went so far as to say, “Family fun is as necessary to modern living as a kitchen refrigerator” (Quotes 57). Nevertheless, there are those who focus on tearing down what Disney, for many, represents by pointing out moral flaws or unfounded innuendoes. In such an imperfect world, unclean things can be imagined even in the purest of mediums, even (and some would argue, especially) in Disney's animated films. However, the viewer cannot discount the values and faith that have shone throughout Disney history. From Snow White's humble prayer in 1937 to the belief in a higher power in 2001's Atlantis, and from Pinocchio's quest in 1940 to find his father and become a real boy to the themes about family in 2002's Lilo & Stitch, Disney animated films are full of moral themes and LDS symbolism.

Walt Disney was a moral man. Despite past and present hashing from critics and competing studios, the man behind the mouse had definite standards and ethical views. Disney once stated, “I have watched constantly that in our movie work the highest moral and spiritual standards are upheld” (Quotes 82). He believed it was worthwhile to make films about family and values. These and other beliefs led to Disney’s nearly impeccable reputation for creating quality family entertainment. Throughout the history of Walt Disney Pictures, there have been several moral and religious themes, including prayer, family, infinite worth, listening to the Spirit, and faith, interwoven, however subtly, throughout their animated films.

From Disney’s earliest ventures into feature-length animation, prayer has played an integral part in the characters and their stories. As far back as 1937, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs displayed a humbly praying protagonist, thanking God for the dwarfs’ kindness to her after her ordeal with family trauma. Three years later, Gepetto dropped to his knees and wished on a star to give life to his marionette creation.

Besides prayer, the importance of family has always been a common theme in Disney films. To quote Mr. Disney himself, “the most important thing is the family” (Quotes 57). Dumbo’s relationship with his mother still brings tears to viewers’ eyes, as does Bambi’s with his. Simba’s relationship with his father Mufasa and his mother, Sarabi, is a clearly functional and happy one. Hercules had not only one set of loving parents, but two (earthly and heavenly). Mulan was willing to sacrifice her life and honor to protect her aging father and serve in his stead in the Chinese army. Indeed, Tarzan contained obvious hints at “Two Worlds, One Family”, how Tarzan could love his adopted family and still continue to learn about who he really was. Probably the most poignant examples of family bonds exist in 2002's Lilo & Stitch and Treasure Planet. Probably anyone could tell that ohana is Hawaiian for family after watching the former. Noteworthy is Lilo and Stitch’s depiction of a dysfunctional family in a home broken by death of parents, and its gradual repair due to strenuous circumstances. Similarly, Jim Hawkins is a damaged teen, and his mother an exasperated single parent, both having been abandoned years earlier by their father and husband. How both of these families pick up the pieces in their stalwart attempts to salvage their relationships speaks to modern audiences.

Infinite worth, a common religious theme, is also commonly woven into the films Disney produces. The idea of a disguised protagonist, a seemingly average person with a lot more to offer has reappeared several times. Cinderella’s title character from 1950 is the Disney version of the scullery maid with a slightly more glamorous past, as well as a dazzling future. The Prince learns there are a lot more important things to relationships than royal blood. Snow White has a similar dilemma, disguised in rags by a jealous and bitter stepmother. Lady and the Tramp’s leading man (dog) learns his value as more than a common stray as he finds himself worthy of a high-class cocker spaniel’s attention. Young King Arthur, in 1963's The Sword in the Stone, realized his pre-ordained worth as the heir to the English throne. Beauty and the Beast was the quintessential story of true worth, regardless of appearance. This reappears in The Hunchback of Notre Dame, as France regards the “ugliest man in Paris” as a hero. Even in The Emperor’s New Groove, Emperor Kuzco learns the value of even the most humble of peasants. Perhaps the most obvious film that incorporates this theme is 1992's Aladdin. The title character, a “diamond in the rough” learned that the only things that discouraged his future with the princess of Agrabah were tradition and law. No amount of wishes could have made him more worthy of an individual, and no quantity of magic could have made Jasmine love him any more.

In addition, throughout the history of Disney animated films, the idea of a divine or heavenly Spirit that guides characters in their choices resurfaces several times. Jiminy Cricket, dubbed Pinocchio’s official conscience by the Blue Fairy was the obvious still, small voice that guided Pinocchio in what decisions he should make. The same type of character reappears as Timothy Mouse in Dumbo. Sebastian and Flounder provided some kind of moral base for Ariel’s teenage rebellion in 1989's The Little Mermaid. Whether or not he was heeded or even welcome, Zazu was a sort of voice of right and wrong to young Simba and Nala in The Lion King. Perhaps the most evident example of listening to the Spirit exists in Pocahontas, when the title character is instructed by Grandmother Willow to “listen with [her] heart” so the spirits around her would guide her down the right path. Arguably the spirit of Pocahontas’s mother, the swirling leaves and native symbols appeared when Pocahontas had a particularly difficult decision to make or crossroad in her life. A swelling fills her soul and heart, as the viewer witnesses the light appearing in Pocahontas’s eyes.

Finally, themes of faith abound in Disney animated films. While nearly all of the aforementioned themes tie into faith, there are several direct examples of belief in divine assistance. Walt once said:

Faith I have, in myself, in humanity, in the worthwhileness of the pursuits in entertainment for the masses. But wide awake, not blind faith, moves me. My operations are based on experience, thoughtful observation and warm fellowship with my neighbors at home and around the world (Quotes 57).

This foundation reappears several times throughout the history of Disney films. “When you wish upon a star, your dreams come true” seems almost a declaration of faith in a higher power. All it takes to be able to fly with Peter Pan is faith, trust and pixie dust. In 1977's The Rescuers, the wizened cat Rufus tells the orphaned Penny that faith is what makes things turn out right. Indeed, several messages to do with prayer, family, worth, the Spirit, and faith abound in Disney’s animated productions.

Besides moral and religious themes, there are several very symbolic films that seem to relate directly to doctrine and history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. While many of the forty-plus animated films produced by Walt Disney Feature Animation contain glimpses of LDS theology, there are a few that seem perfect allegories for the latter days. Pinocchio, Alice in Wonderland, The Lion King, The Hunchback of Notre Dame and Hercules are among the most noteworthy.

Pinocchio, released on February 7, 1940, reveals one of the most perfect allegories in the history of film of man’s journey through life. Indeed, a copy of this film rests in the cornerstone of the Orlando, Florida LDS temple. Pinocchio’s is the story of a child, created by a father figure, and given life, a spirit, and a conscience. He is requested to be brave, honest and noble, put others before himself and to always let his conscience be his guide. From the start, the naive and innocent wooden boy has the purest of intentions. He wants to go to school and be good on his path to being a real boy, but he is soon led astray by the deceitful glitter and glamour of fame, fun and indulgence, all of which lead him to misery. His lack of integrity, due to fear of consequences, shows as his nose lengthens with every lie he tells. When Pinocchio falls into the clutches of Stromboli or gives into the temptations of Pleasure Island, he realizes he should have listened to his conscience. Jiminy Cricket, while sorrowing for Pinocchio, can do nothing to prevent the consequence that must accompany the protagonist’s actions. It is only when Pinocchio learns of his father’s mortal danger that his heart is changed and he sacrifices everything for him. He searches for him over land and sea, all while bearing the scars of his mistakes, but more importantly, using what he has learned to prevent him from further mishap. All the way into the belly of a lethal whale, Pinocchio ventures to find his father. When he eventually risks his life, heart, and soul for the father who created him, it seems as though Pinocchio has made too many mistakes to become a real boy. The blue fairy, nevertheless recognizes his growth and unconditional love for his father and grants him the grace to know and realize his true potential. This is a definite parallel to the LDS views on life and divine identity. The gospel teaches that even apart from all we can do, we are still imperfect and unworthy of the eternal life, but if we love God, He will give it to the humble-hearted person who accepts Christ as his redeemer. Truly an inspirational story, Pinocchio

In the bizarre Alice in Wonderland, released July 28, 1951, Alice’s journey through Wonderland, while unusual and idiosyncratic seems a metaphor for the individual’s journey through life. She starts out at home with her cat and her sister in a comfortable haven, safe from the outside world. Naive and fairly content, Alice is nevertheless bored and dissatisfied with her lot in life, until she follows the strange and mysterious White Rabbit and starts her journey through Wonderland. Curious and unsettling as it is, Alice learns a great deal from her encounters. She learns patience from the Cheshire Cat, the Caterpillar and the hosts of the Mad Tea Party. She learns respect and dignity from the Flower Garden. She learns integrity from the less-than-honorable playing cards, painting the roses red and blaming each other when the Queen of Hearts demands to know the responsible culprit. She learns humility as she realizes she’s not a perfect little girl and must rely on the help of others to guide her through Wonderland.

Alice receives guidance, reliable or otherwise, and learns the value of considering where the impressions come from. She has her ups and downs and her highs and lows as she grows several feet higher and shrinks to just a few inches tall, indicating an emotional roller coaster on her trek through life. Certainly Alice learns a great deal from the abusive and outspoken Queen of Hearts and her mild-mannered, timid husband. In the end, Alice faces the final judgment at the Courtroom amid wars and rumors of wars as the Queen’s madness drives the entire population of Wonderland into argument and contention until it’s a blinding mess of color and dissension, an allegory of the modern world’s conflicting views and beliefs. Ultimately, Alice reawakens as though from a dream to the world that she knows and loves. Surely she had learned a great deal, including gratitude for the comfort and safety of her home. Alice eventually made it back home, if not by difficulty and even pain.

The Lion King, released June 24, 1994, is a favorite among youth speakers in the church and devotional givers, and for good cause. Definitely full to the brim with LDS implications, this is the story of the son of a king. As everyone on earth is a literal child of Heavenly Father, this is a perfect allegory for anyone. Trouble befalls young Simba as he feels like his father is gone just because he’s died. He is deceived by a close relative, led to believe he is no longer worthy of his divine parentage. When Simba escapes into the world, he is taught half-truths, ultimately shallow and unfounded doctrine. Though lies becomes imbedded into his mind, he finally faces his true identity when the voice of reason, via his childhood best friend and betrothed queen Nala, confronts him and begs him to reclaim his heritage as a king. Only when the figure of spirituality, Rafiki, appears and shows him his reflection does Simba realize who he truly is. As the young heir to the throne looks at his reflection, he sees he can become like his Father. Simba then receives personal revelation that in forgetting his own royal identity, he has forgotten the Father that left it to him. Mufasa’s words echo in the night sky, “Remember who you are. You are my son. . .” Ultimately, Simba faces who he really is and the fears and doubts he had about himself wash away with the cleansing rain that follows his victorious battle against evil. Every person on earth has a similar destiny if they only remember who they are and keep their Heavenly Father foremost in their minds and hearts.

While The Hunchback of Notre Dame, released June21, 1996, received mixed reviews, it is nevertheless a film full of LDS symbolism. Quasimodo, a victim of social grudges and misconceptions, is a subservient follower of Frollo, a man he believes to be righteous and caring, but who is no more than a hardened hypocrite. The character of Esmeralda is undoubtedly a symbol of purity twisted to evil by demented minds. Phoebus’s character is particularly noteworthy, as a borderline character, working for the bad side, but ultimately leaning toward the good. When he realizes he’s heading down the wrong path, he dismisses the influence of evil in his life, refusing to burn down an innocent family’s windmill. As Frollo condescends to do the dirty work himself, during Pheobus’s escape, the burning windmill forms the shape of a cross, a symbol of destruction of the innocent. When Phoebus falls into the river, wounded by an arrow, he is wearing full armor. He appears to die as something of a martyr, but is saved by the grace of Esmeralda, again, a symbol for purity of soul. When she pulls his body from the river, his armor is absent, and he’s wearing full white, a symbol of his baptism and repentance for the wrong he had done. Later, during Frollo’s attempt to burn “the witch” Esmeralda at the stake, he appears in his usual black robes, while Esmeralda follows suit after Phoebus and dons all white, an appropriate indication of baptism by fire. Quasimodo sacrifices his life and loyalty to an evil master to save those he loves and is consequently welcomed into the open arms of the public. There is much to be learned from this relatively controversial Disney film, despite the arguments against it.

Finally, and in perhaps the most blatant example of LDS ideology in Disney animated films, Hercules, released June 27, 1997, tells the story of a boy born to Heavenly parents, sent, however unwillingly or unknowingly, to live a mortal life on earth. His earthly parents provide the nourishment and comfort a child needs to survive, while noticing the remnants of his divine heritage, his medallion and his strength, or his undeniable spirit. As a teenager, Hercules finds he just doesn’t feel right about any situation he’s placed in and knows there must be more to his life than what he has. He desires nothing more than to “Go the Distance” and find where he belongs. He decides to go on a journey to a sacred place and pray to know what is the truth. In the temple of Zeus, Hercules finds the statue come to life. It informs him of his divine heritage and everything he can accomplish if he has his true identity in his heart and mind. This revelation has often been compared to Joseph Smith’s First Vision. Young Joseph Smith knew there was something missing from the life he was living, and went to a temple of sorts, the Sacred Grove, to learn the truth, whereupon he received the information he prayed for.

Walt Disney may have had his flaws in his business ventures, and even in his personal life. Truthfully, no one’s perfect. However, through Walt Disney’s trials and experiences, it seems evident that before his untimely death, he had learned a great deal of what’s truly important on this earth. “I believe firmly in the efficacy of religion, in its powerful influence on a person’s whole life. It helps immeasurably to meet the storm and stress of life and keep you attuned to Divine inspiration. Without inspiration, we would perish” (Quotes 82). These ideals became apparent as early as 1937 and 1940 with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Pinocchio and as late as 2002 as the Disney legacy lives on through Lilo & Stitch and Treasure Planet. Whatever faults he had, Walt Disney had a definite moral streak that shone through his work and his words.

All the adversity I've had in my life, all my troubles and obstacles, have strengthened me... You may not realize it when it happens, but a kick in the teeth may be the best thing in the world for you. -- Walt Disney

To prove I'm not the only one who thinks this kind of thing about Disney films, check out the following titles:

The Gospel According to Disney: Faith, Trust, and Pixie Dust

The Gospel in Disney: Christian Values in the Early Animated Classics

Back to the theories page or head back to the Heroes homepage.